Fame and Glory

Burke and Wills were 19th century explorers in Australia. Burke and Wills had over a thousand miles of horrifying desert to cross. They made it, but this story does not end well.

A dying kangaroo squats in the red dirt road. Head drooped, front paws limp, it can barely hop out of the way. The sun, an evil globe scorching the Australian bush, is cooking the meat inside the kangaroo’s tattered fur. I pull over, pour several quarts of my emergency water into a makeshift bowl, and set it beside the road, but I know it’s too late.

The drought is that bad. Kangaroo carcasses dot the desert like the skeletons of dead explorers, their hides stretched taut over rat-gnawed bones, sand drifting into their pecked-out eyes.

I stop for the night in Tibooburra (population 130), a ghostly, dirt-blown town 600 miles north of Melbourne in the northwestern corner of New South Wales. The Tibooburra Hotel is a dilapidated two-story sandstone building with a peeling wooden porch. Tiny rooms above the pub, bathroom down the hall. I am the only guest.

In the pub: a prosthetic leg and a dusty saddle hang from the ceiling, cowboy hats are nailed in rows along the walls, the smell of cigarette smoke in the air. I order a mug of beer that immediately goes warm.

A crooked little man in a crushed Aussie cowboy hat bounds through the screen door, takes a stool at the bar, pours a mug of beer down his creased, stubbled throat, and orders another.

“I’m the water hauler,” he volunteers.

Turns out Tibooburra, an Aboriginal name meaning “heaps of rocks,” went dry two years ago, and locals have had to truck drinking water in from an aquifer-fed reservoir.

“A third of an inch of rain in two years, that’s it,” says the Pooh-bellied bartender.

“We got a 3,000-gallon tanker now,” the water hauler crows, raising his mug to me. “Goin’ tomorrow 3 a.m. for the fill-up, mate, if you care to come along.”

“Thanks, but I’m heading to Innamincka,” I say, “to see the Dig Tree.”

The Dig Tree is a gnarled coolibah tree that stands in the burnt heart of the outback beside the warm, green water of Cooper’s Creek. It is the most famous tree in Australia, on account of the cryptic instructions carved into its trunk and the part it played in this country’s most notorious expedition.

In 1860, Robert Burke and William Wills set out to become the first white men to cross Australia, a historic south–north traverse from Melbourne to the Gulf of Carpentaria, right below Papua New Guinea. Their eight-month journey took them through the Tibooburra region in October of that year, en route to a base camp on Cooper’s Creek, and then onward into vast, desperate stretches of the interior. Burke and Wills are the Lewis and Clark of Australia, famed icons of early continental exploration—although, by the time it was all over, they’d become legends for very different reasons.

“Burke and Wills—now they were some bloody tough bastards!” says the bartender, suddenly animated. “I hope they’re still teaching the schoolchildren about our heritage.”

To get a taste of what they experienced, I’ve driven up from Melbourne to the desert in the dead of summer—January—after one of the driest years in Australian history.

“Tracin’ their path, are ye?” says the water hauler. “Bugger, they was brave.”

The Australia that Burke and Wills ventured into was an immense, uncharted continent. Roughly the size of the U.S., it had been the home of Aborigines for 60,000 years when, in 1788, a British penal colony was established near present-day Sydney. By 1860 there were one million European immigrants living on the coastline; but two-thirds of the continent, including the entire western half, remained unexplored (by white Europeans, that is; Aborigines had been following their song lines across the outback forever).

Discovering what lay inland had far-reaching implications for communication and commerce. It took two months for news to travel by ship from England to its Australian colony, and yet a telegraph line already extended from Europe to India to Southeast Asia. What if a line could be strung from Melbourne, the major port on the southern coast, straight through the outback to the northern coast, and linked by cable with Asia? World news would take a mere two hours to get all the way Down Under.

Members of the Royal Society, a Melbourne gentlemen’s club composed of white scientists, businessmen, and armchair explorers, took it upon themselves to solve the mystery of Australia’s frontier. In January 1860, they announced plans to fund the Victorian Exploring Expedition and placed an ad for a leader in the Melbourne papers. After much internal politicking, the Royal Society chose Robert O’Hara Burke, 39, a small-town Irish police superintendent, as the expedition’s unlikely leader.

“The idea of Burke leading any expedition anywhere at all was ludicrous,” writes former BBC correspondent Sarah Murgatroyd in The Dig Tree, her 2002 history of the epic journey. “He was neither a surveyor nor a scientist and had no exploration experience.”

Historian Alan Moorehead describes Burke in his 1963 book Cooper’s Creek as a “wild eccentric dare-devil” who was in “no sense a bushman” and “some thought not quite sane” because of his habit of lying for hours in a bathtub in his backyard wearing only a pith helmet.

“Burke was popular, charming, and intelligent, but excitable, impulsive, and headstrong,” writes Murgatroyd. By all accounts, Burke appears to have been guided not by an explorer’s fundamental trait—curiosity—but by two esteemed Victorian values: fame and glory.

(Victorian expeditions would become famous for death and disaster, think on the Sir John Franklin expedition to explore the Northwest Passage in 1845, or the British Antarctic Expedition, led by monomaniacal Captain Robert Falcon Scott to the South Pole in 1911.)

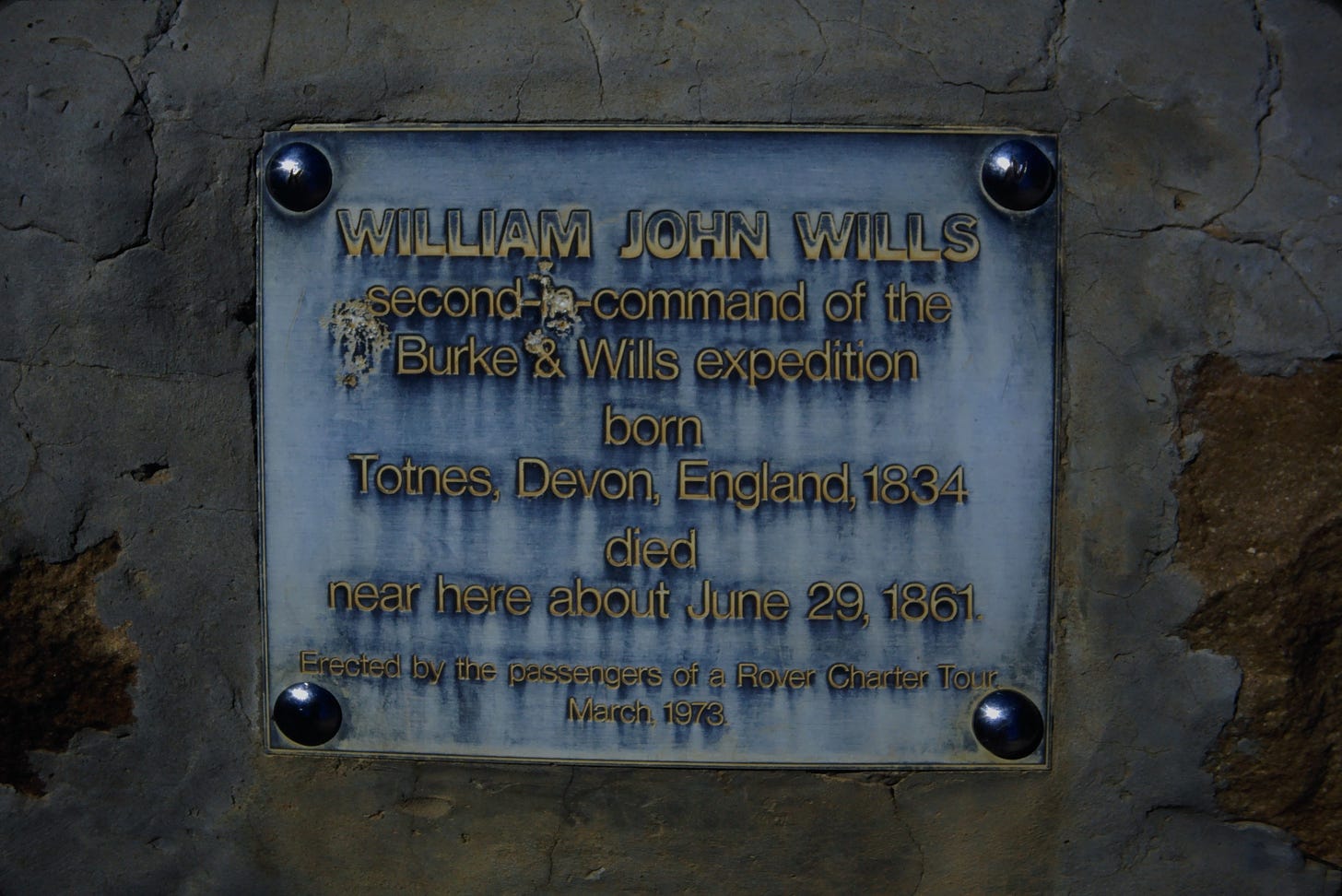

Good thing, then, that the expedition’s 26-year-old surveyor, William John Wills, was a diligent student of cartography, natural history and the sciences. According to his father, he was “ever pining for the bush . . . his love fixed on animals, plants, and the starry firmament.” Wills would become the second-in-command of the Victorian Exploring Expedition. Burke and Wills: a novelist couldn’t have fashioned two more disparate characters.

On August 20, 1860, the Victorian Exploring Expedition left Melbourne, bound for the Gulf of Carpentaria, 1,500 miles of Sahara-like desert to the north. It was a circus from the start: 19 men, 26 heavily laden camels imported from India, 23 horses, a train of six bizarrely overloaded wagons, and a semisubmersible dray. All told, they were hauling 20 tons of equipment and accoutrements, including 12 sets of dandruff brushes, four enema kits, an oak table with two oak stools, and a large bathtub.

As Victorian explorers were wont to do, Burke declared that he would cross Australia “or perish in the attempt.”

The consensus of the Tibooburra pub is that I should stick to the main dirt track to reach Innamincka, a day’s drive through scrub plains and foot-deep bull dust. It’s one of the few regions on earth where it’s possible to die if your car breaks down. You hide out in the sweltering shade of your vehicle, drink your emergency water, and wait for another car to pass by. If no one happens along in 48 hours, you’re cooked. In 1963, a family of five perished this way.

Rejecting their advice, I navigate an obscure sandy path to a watering hole called Olive Downs, where I count 27 kangaroo carcasses locked in the fractured mud. I bump along “jump-ups,” hillocks of rock and sand, and, following a trail that’s no wider than my truck, cross the breadth of Sturt National Park. Named for Charles Sturt, one of only a handful of explorers who preceded Burke and Wills, the desolate country seems little changed since the summer of 1844, when Sturt and several teammates rode horses north from Adelaide into the desert. Some 800 miles inland, Sturt found a network of channels and permanent warm-water billabongs, which he christened Cooper’s Creek, after a South Australian judge.

That same year, 1844, a Prussian named Ludwig Leichhardt walked an astounding 3000 miles from Brisbane to Port Essington along the northeastern coast. But he disappeared on his next expedition, and surveyor Augustus Gregory was dispatched to find him.

Between 1855 and 1858, Gregory made several bold desert journeys including a boomerang-shaped trek from Brisbane, on Australia’s east coast, out to Cooper’s Creek, then back south to Adelaide. Gregory and his men went on horseback, lived off the land, and set a precedent for traveling extraordinarily light---but they never found Leichhardt. Likewise, fellow explorer John Stuart accomplished five successful journeys in the early 1860s, eventually crossing Australia east to west. Stuart also traveled light, with his horse, Polly, and a few saddlebags. In more than 12,000 miles of desert, he never lost a man.

In contrast, the Burke and Wills expedition began falling apart even before making it out of Melbourne. The axles of several sagging wagons snapped and three team members were sacked.

Four weeks later and 250 miles north, Burke realized he was dangerously overburdened. He dismissed seven more men and jettisoned gear willy-nilly—everything from a useless camel stretcher to a store of lime juice, an essential preventive of scurvy. Still, a week later the draft horses were so exhausted they were set free, the wagons left to rot in the bush. Even the camels began collapsing in the heat.

Burke did not keep a diary: he relied on Wills to do so. Wills took copious notes on the flora and fauna, navigated and plotted the team’s course through the desert, and indefatigably tackled the day-to-day headaches of expedition management.

After traveling 465 miles in 56 days—a distance a horseman like Gregory or Stuart could have covered in a mere ten days—Burke reorganized again, leaving five men, tons of gear, and dozens of horses beside the Darling River. The Victorian Exploring Expedition was disintegrating.

Temperatures rose to 140 degrees in the sun, yet Burke ignored the advice of local Aborigines and often passed up shaded watering holes where “bush tucker”—game and desert vegetables—was plentiful. Each day was a 16-hour forced march. The expedition reached Cooper’s Creek, the oasis of the Australian outback, on November 11, 1860.

Innamincka (population 14) is a forlorn cluster of ramshackle buildings beside languid Cooper’s Creek—a gas station in the sand, a pub hidden in the middle of millions of acres of nowhere, a dusty airstrip used to transport oil and gas crews and the occasional mail pouch. It’s the kind of end-of-the-earth outpost that a director might choose for a movie set.

In fact, I book into the Burke Lodge Cabins, a set of three trailers left over from the 1985 film Burke & Wills. As the only guest, I’m given the director’s trailer, which contains four midget beds, a screeching, wall-mounted AC box, and a shower where a snake keeps poking its head up through the drain.

“Out here, it’s either drought or deluge,” explains Joan Osborne. She’s a landscape painter; her husband, John, is a retired aluminum-plant foreman. Together they’re Innamincka’s longest-lasting residents and unofficial mayors. They are accustomed to the otherworldly calamities of the outback.

“Some years, the flies are so bad, your food is black if you try to eat outside,” says Joan. “For a few years, we had a rabbit infestation which meant there were lovely wedgetailed eagles everywhere. Things don’t change here so much by season, as by years. We had a stretch where it rained so much, Cooper’s Creek was constantly flooding.”

“This year, it’s snakes,” John tells me, his face tan as dark sand. He’s wearing traditional outback attire---sweat-soaked t-shirt, ratty shorts, slip-on boots. “Eight-foot king brown bit a mate. Came through the ductwork and dropped onto his bed. Bite nearly killed him.”

So why do they live out here?

Joan sighs, disappointed that I haven’t figured this out for myself.

“It’s so beautiful.” Her eyes almost water. “There is nothing like the desert. Nothing in the whole world.”

Because Cooper’s Creek had permanent water in the billabongs and ample shade under the coolibahs, it was a center of commerce for the Aborigines for a thousand generations. They would travel hundreds of miles to trade shields, wooden bowls, ax heads—or simply to socialize.

When Burke and Wills arrived at Cooper’s Creek, they were welcomed by the Yandruwandha Aborigines with offerings of fish and invitations to ceremonies. Burke rebuffed them by blasting his pistols into the air.

Summer and its mortal heat had descended. The Yandruwandha warned Burke not to venture farther into the desert during the hottest months, but he was insistent. He ordered four men to stay behind at Cooper’s Creek to guard a stock of provisions against a plague of rats. They were instructed to wait three months for Burke’s return—until March 15, 1861—before forsaking the post.

On December 16, 1860, Burke, Wills, and two other men—an ex-soldier named John King and an ex-sailor called Charley Gray—strode defiantly into the unknown. They took six camels, one horse, and three months of food. The terrain varied from dismal rows of dunes to baked claypan, rock-tiled wasteland to savage, waterless mountains. On some days, Burke and his men managed only five miles; other days they slogged 35 miles or more across the punishing bush.

Through inhuman persistence, Burke and Wills reached the Gulf of Carpentaria, along Australia’s northern coast, on February 9, 1861. But they never even saw the ocean. They marched until they were knee-deep in a mangrove swamp, then simply turned around. The Victoria Exploring Expedition had triumphed—although what began as “the finest expedition ever assembled in Australia” was now down to four emaciated men in rags. And it was 900 miles back to Cooper’s Creek.

“Ya see, mate, they weren’t Aussie bushmen, now were they?” Bomber Johnson chides, wiping his forehead with a neckerchief in the 110-degree shade.

Red-faced, yellow-haired, bushy brows falling into his eyes, 69-year-old Bomber is the self-appointed historian and personal guide to the Dig Tree, a 44-mile drive north from Innamincka along a twisting sand track.

“They were arrogant. They didn’t try to learn from the Aborigines,” says Bomber. He’s a jackaroo (Aussie for “cowboy”) who has spent 35 years mustering cattle in his Cessna 172.

Bomber tells me stories about Aborigines: the trackers who could follow outlaws across bare rock by finding the grains of sand that fell out from beneath their toenails, the jackaroos who could survive on goanna lizard flesh for weeks. “They knew how to live in this nice big slice of hell,” he says appreciatively.

Bomber directs me to an unassuming coolabah tree distinguished only by an encircling boardwalk. Carved into the twisting trunk are the letter B, for Burke, and the roman numerals LXV, for the expedition’s 65th camp. Over the last century, Bomber explains, folds of bark have covered up the most famous inscription:

dig

under

3 ft nw

april 26, 1861

On February 13, 1861, Burke, Wills, Gray, and King began dragging themselves southward from the gulf. With supplies almost gone, Burke cut rations in half. Although Wills was a good shot and King would later report that they were surrounded by “kangaroos, emus, and any quantity of ducks and pelicans,” Wills was now too debilitated to hunt.

Burke, by this point, had likely gone mad. Once, when a camel dropped and couldn’t continue, he inexplicably abandoned the beast instead of eating it. On March 15, 1861, the day they were due back at base camp on Cooper’s Creek, Burke and his men were still 680 miles to the north. Burke cut rations again. They were drinking three quarts of water a day, when their bodies needed ten, and burning twice the number of calories they were consuming.

Gray began lagging behind, his legs in excruciating pain. He became delirious and then unable to speak. He died at sunrise on April 17, 1861, less than 100 miles from Cooper’s Creek.

Four days later, Burke, Wills, and King stumbled into Cooper’s Creek and, upon seeing the inscription in the coolibah tree, collapsed. King felt the still-warm ashes of the campfire. The four men at base camp had waited an extra five weeks at their post but had left that very morning.

After eight months of unspeakable hardship, Burke, Wills, and King had missed salvation by eight hours—and now were too exhausted to catch up.

Buried beneath the Dig Tree in an old camel trunk were stores of flour, sugar, tea, and dried meat left behind by Burke’s men, but it wasn’t enough. Robert Burke and William Wills died of starvation and exhaustion beside Cooper’s Creek. In September 1861, King was found living with Aborigines near Innamincka. Of the men left behind along the way, five perished, most of them from scurvy.

They are still teaching the Shakespearean tale of Burke and Wills to Australian children, whereas Sturt, Gregory, and Stuart—efficient and capable, paradigms of exploration—were consequently forgotten. Tragedy and irony always play better than common sense. We humans adore martyrs, as long as we don’t have to be one.

The five rescue missions dispatched to find Burke, Wills, and the stragglers from their party further opened the Australian interior. On August 22, 1872, the first telegram was sent from London to Adelaide, passing through an underwater cable from Java to present-day Darwin and then across the blazing expanse of outback.

A few miles northwest of Innamincka, on the banks of languorous Cooper’s Creek, there is a concrete cairn marking Burke’s grave. As I stand before it in the dizzying heat, swatting flies and staring at the simple plaque, it occurs to me that, in the end, Robert O’Hara Burke got exactly what he so wanted.